Colonial and Old Time Social Dance Tunes in Australia by Peter Ellis

Supported by the Folk Song and Dance Society of Victoria

Social Dance Music – Australian Colonial & Old Time

I have assembled this compilation of Australian collected dance tunes under the title ‘The Waltz, the Polka and all kinds of Dance Music’ as a theme from the line of the song ‘Augathella Station’ and because of the momentum of interest in Australian material in the folk scene. Also, the Bush Dance and Music Club of Bendigo Inc. has produced a range of double CDs called the ‘Quadrille Mania’ series, as well as the ‘Waltz, Polka and all kinds of Dances’ triple CD. These CDs include a cross–section of tunes which the musician can play and accompany at correct tempo and style. This endeavour has provided an opportunity for players to hear some of the tunes collected since my last books were compiled and particularly Collector’s Choice Vol. 1 published 1986 by the VFMC which focused on the old collected dance tunes of town and country. Some tunes from other collectors are included for interest and to provide broader interstate representation and in particular, where the piece is so good, as an excellent tune type example.

Additionally an enormous volume of tunes has now been assembled through the resources of collectors such as John Meredith and Rob Willis, and the efforts of other musicians such as Dave de Santi and Ray Mulligan. Despite this it needs to be remembered however that most traditional musicians had far more popular material in their repertoire, which perhaps is overlooked, and that our specific collections tend to give a different concept of tune selection. For that reason I have cross referenced as much as possible the popular, even classical, tunes and other overseas material to which our dance music is linked.

Whilst our pioneer folk musicians contributed their own tunes from various homelands of origin, there is an impression that migrants from European countries also introduced their folk dances as they arrived on the goldfields. The truth is, as my Grandmother used to say, ‘it is all the same in a hundred years’, and our forebears were as much influenced by the latest fashion and craze, then, as now. The Waltz, Polka, Galop, Quadrille even Mazurka, Varsoviana and Schottische and their music made their society debut in Europe and England and had arrived within months in America, Australia and the other Colonies. This had occurred before and up to the 1850s gold rushes and the arrival of waves and waves of immigrants. Except for Governor Macquarie’s blessing, the Waltz had ‘taken’ Sydney by 1815, soon after Waterloo and the Quadrille was well established by the early 1820s with a special Australian arrangement in 1825 (La Sydney (fig. 1), La Woolloomooloo (fig. 2), La Illawarra (fig.3), La Bong-Bong (fig.4), La Engehurst (fig.5). The Galop of 1829 was here within a year of its debut in Europe as there is a description of a Perth ball in 1830 in which ‘gallopades’, (another term for the galop), were danced. (The other gallopedes, longways sets, developed later from the Galop or Gallopade) Also a Goulburn Baall program included the Polka in the same year as it was first described in the London Illustrated News of 1844. Even the Irish, who counted for on third of the immigrant population by, or following the potato famine of the 1840s, were as much au fait with the music and steps of the above dances as their own jig and reel.

It was not until after Irish independence from Great Britain in the 1920s, and when dances and tunes of outside origin, were banned that much of their own dances and music were compiled into collections, as we are now doing with Australian material. The new branch of the Gaelic League in Ireland in the 1890s discovered that few old dances apart from step dancing had survived. To gain standing comparable with the Scottish branch of the League that had recognisable traditions, they orchestrated the invention and introduction of new Irish dances under a type of smoke and mirrors revival of the ‘old style’. As an example, the Siege of Ennis with Irish stepping was choreographed from the old La Tempete of the English and European ballroom. (Nothing’s new, the Australian New Vogue fraternity do this all the time under the ‘Old Time’ umbrella and likewise the ‘Bush Dance’ concept of the 1970s revival is an equally flawed concept of our pioneer rural tradition. ) Nevertheless this stage of history has resulted in a very rich tradition of respective dancing in Ireland and Australia, but it wasn’t there in the mid–nineteenth century when they were simply dancing quadrilles, waltzes, polkas, redowas and schottisches, all the fashionable dances of the day – as did everybody, and yes, the English Sir Roger de Coverley, the Irish Jig and the Scotch Reel. Significantly, some of the best teachers of the ‘Waltz, Polka and all kinds of Dances’, and fiddlers of this music in Australia, were the Irish. Likewise some good dances have come from the New Vogue scene and the 1970s Australian Bush Dance revival has many positive benefits.

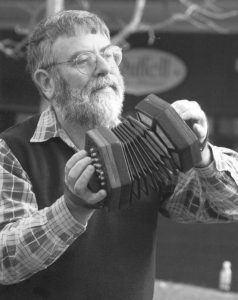

Taking that into account as well, it has been my aim to try and highlight some of the individual musical nuances of our traditional dance tunes. At the same time I’m the first to acknowledge there are always exceptions to the rules and also many shades of grey. But it wasn’t necessarily the musician’s whim that allowed a tune of exception or the shade of grey in its performance for a dance, as distinct perhaps from an item. If it wasn’t suitable for dancing, it wouldn’t get past the MC (Master of Ceremonies). His absolute authority is something that all in the folk scene need to take into account as well as his discretion as to whether a new dance, regardless of latest fashion or folk dance from someone’s homeland, would be included on a program. Even at private house parties in the bush, people still had their dancing pumps and a nominated MC as well as someone in the family that could play violin, piano or squeezebox and there were all the usual protocols even at an impromptu family dance.

The rural musicians weren’t academics and the concept of differentiating between a traditional tune such as the Irish Washerwoman or the Connaughtman’s Ramble and the pseudo Irish tune such as McNamara’s Band wouldn’t come into the equation. If they liked it, a good tune was a good tune and all that mattered was that it suited the dance.

I’ve tried to illustrate things like suitable music for the polka and that anything in 2-4 is not necessarily a polka, or suitable, for our dances even though it might be perfectly acceptable in the revived Irish tradition. At the same time, our musicians simply knew what to play – they would not have known the term single reel or single jig, but neither would they randomly call 2-4 tunes ‘polkas’. But they would have a considerable range of set tunes up their sleeve, listed as Lancers, First Set or Alberts tunes, or just ‘set tunes’ as wellas tunes for the Polka, Waltz etc. Likewise, the dance musicians of the towns that generally used sheet music, nevertheless knew instinctively how to play the tune by cue nominated on the sheet music:– ‘tempo di Schottische’, ‘tempo di polka’, ‘tempo di mazurka’, etc. It was an essential part of their training as dance musician (see example page 113 – Golden Stream Varsoviana “Tempo di Varsoviana”)

Sometimes the terms are related to the dance steps rather than the musical category. Thus a tune for a step–dance might be called a jig because it’s a ‘jiggy’ dance, whereas musically it might be a reel or hornpipe. The dances of the Old Time Medley, Varsoviana, Polka Muzurka, Highland Schottische and Polka (3-hop), in that order and combination, and sometimes including the Two Step, were also known as the ‘Polkas’, but only the 3-Hop Polka is really a polka with true polka tunes. Polkas applied to them collectively as a medley because they were ‘hoppy’ dances, but the music is very different for each special dance with a specific style tune for each.

Bush dance and bush music was not a used term either and there was probably little difference between a district player and one in town. However the towns were quick to take on the latest such as the One Step and the Foxtrots, whereas the older traditions persisted in the bush, and like a national identity, we tend to reflect on our country’s rural heritage and our past and today bush music is an appropriate term. It doesn’t mean every aged fiddle or squeezebox player was a good dance musician, some were pretty terrible. But an enquiry through the local community and district MC would always lead to the reputable and revered dance musician. Following these leads has certainly come out in collections such as those by John Meredith. Likewise in the towns and cities, some dance bands, usually three or four piece (called orchestras) were mediocre, but the top bands could ensure the success of a dance or ball simply with their loyal followers. Those like Ma Seal, Bert Jamieson, Joe Yates, Harry Cotter, Charlie Batchelor, Joe Cashmere, the Dawsons, Dooley Chapman, Elma Ross and many more, are legends, national treasures, and it was always said at a dance where Harry McQueen and or Bill McGlashan played, anywhere else would be a poor night.